|

The number of people representing themselves in court is increasing.

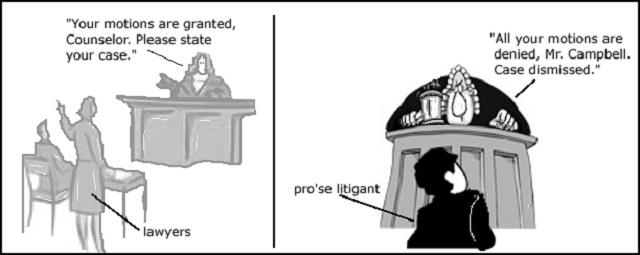

It isn’t easy, and pro se litigants almost always lose. This isn’t because they don’t have a good case or aren’t prepared; it’s because judges automatically rule against them and in favor of their fellow club members (fellow attorneys).

There is an interesting development in Washington State…

Unraveling a 23-year marriage is no simple thing. Kerry Rayder understood that, but she also thought her amicable divorce should be uncomplicated. In 2013, her daughter was 17 and nearly out of the house. The family had no major assets aside from a Fort Collins home and shared retirement benefits from her husband’s job.

Rayder had been warned that divorce attorneys could charge up to $10,000 per person, which seemed like an outrageous price to pay for someone to fill out some forms and make one court appearance. A co-worker had gone the DIY route in her divorce, and 53-year-old Rayder, possessed of a quiet but determined demeanor, figured she could too. Her job requires her to dig through complex medical forms to produce health-care reports, so she’s comfortable with legalese.

After attending two divorce self-help clinics, though, Rayder wished someone would post these kinds of legal tutorials on YouTube. There were only about 10 people at each session, but the presenter spent most of the time catering to attendees’ wildly varying, situationally specific questions—on everything from domestic violence to complex property rights—and those sidebars didn’t really correlate to Rayder’s case. When she tried to complete court forms online, they were incompatible with her Mac, so she spent hours amid stacks of paper, filling the forms out by hand.

In court, the judge reviewed Rayder’s application and made some quick adjustments; the process was done in just four months. Rayder went about starting her life anew but soon realized she wasn’t receiving any information about her expected retirement benefits. She’d filled out the correct form, but for some reason the court didn’t have it. If she’d forgotten to put it in the stack, the judge hadn’t noticed, and no one at the courthouse flagged the missing document.

This forced Rayder to file an amendment to the original separation agreement. It was exactly what she’d hoped to avoid—spending more time sorting through her emotional detritus—but thanks to the paperwork error, she and her ex had to revisit the pain of their separation. Why, Rayder kept wondering, couldn’t this process be more like filing your taxes online, where if something’s missing, the system sends up a red flag and everything stops? And why wasn’t there a cheaper option for people like her?

Rayder is not alone. The questions she had are common enough that they’re disrupting the way civil law is practiced in Colorado. That’s because the number of “pro se” litigants—people who appear in civil courts without attorneys—is rising. Some, like Rayder, suffer a few hiccups and clog up the courts. For others, much more is at stake.

In the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, America’s founders established “justice” as a fundamental tenet for the young nation in the first 17 words. Scholars, politicians, and courts have subsequently spent more than two centuries bickering over what justice actually means. As the principle has endured, it’s also created a complex legal system that’s resulted in more than 1.3 million American lawyers who try to help citizens navigate our courts as advocates.

|

In Colorado, family law attorneys can charge between $200 and $500 per hour; top corporate lawyers can cost more than $1,000 per hour. The rates are fueled, in part, by the high cost of getting a law degree—public law school graduates carry an average of $84,000 in debt, and private law school alums can have more than $120,000—and by demand (most people believe they’re more likely to win in court with a lawyer by their side). And while our court system was never intended to require an attorney’s help for every matter, over time the implications of appearing without one have troubled many: judges, attorneys, and the public. That’s one of the reasons why the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Gideon v. Wainwright and 1964’s Criminal Justice Act ensured that in criminal court, every defendant would have access to a taxpayer-funded public defender.

These changes don’t cover civil courts, even though someone’s basic needs—such as losing a home to foreclosure—might be at stake. And although there have been national- and state-driven efforts to provide free representation in civil matters, they’ve often focused on the funding of low-income-qualification legal aid programs, such as Colorado Legal Services (CLS). In 2014, CLS served more than 13,000 parties. For every person CLS helped, though, lack of resources forced it to turn away another. (For comparison, there are more than 400 criminal public defenders in Colorado but only about 50 attorneys at CLS.)

Funding for these programs has declined in recent years as the number of pro se litigants from all income levels has increased. In 75 percent of Colorado’s domestic cases in 2013, neither party had an attorney. The issue isn’t limited to family law; the numbers of bankruptcies, landlord-tenant disputes, and social security appeals with pro se parties are also rapidly growing. “Lawyers have priced themselves out of the market for most middle-class working people,” says CLS executive director Jonathan Asher.The gap between what attorneys charge and what people can pay is often vast. A recent report on pro se litigants from the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS), a University of Denver–based think tank, found that more than 90 percent of respondents wanted attorneys but couldn’t afford them. Judges reported that pro se litigants put the outcome, and the fairness, of their cases at risk. “Sixty percent of judges reported an increase in self-representation immediately after the recession,” says IAALS executive director and former Colorado Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Love Kourlis. “However, the effects linger to this day. It may have been spurred by the recession, but it has not abated in any way.”

On January 22, 2016, about two dozen people met at the Colorado Bar Association. Many had an Esq. after their names and had fought legal battles in and out of courtrooms. On that day, though, the orators appeared to be stalled. They were part of the Colorado Supreme Court Advisory Committee’s investigation into whether the Centennial State should adopt the use of limited license legal technicians, or LLLTs.

The relatively new job description is the legal world’s equivalent of a nurse practitioner, a sort of paralegal on steroids who is highly skilled but less expensive than an attorney. Last year, Washington state became the first to implement an LLLT program when it began licensing legal techs (there are 10 so far, and hundreds of LLLT-focused students are in the community college pipeline). Many of the would-be legal techs will—after earning an associate’s degree, taking three certification exams, and completing 3,000 work hours under the supervision of an attorney—potentially make much more than paralegals while still billing as little as $60 an hour.

Washington’s LLLTs are limited to working on fairly simple domestic cases and cannot appear in court. They are also legally obligated to refer clients to attorneys when matters get too complex—for instance, dealing with Rayder’s missing retirement benefits form—which helps ease malpractice concerns. As a result, several LLLTs are actually working in law firms. “Lawyers see this as a business opportunity instead of a threat,” says attorney Steve Crossland, the chair of Washington’s LLLT board. “They see that it can bring more business into the firm that might otherwise not be there.”

Not everyone is convinced. Detractors still worry about malpractice implications and whether LLLTs would take business away from attorneys who’ve invested a lot of money in their educations. Or they wonder if these solutions might actually negatively impact people’s access to justice by not connecting them with attorneys. Loren Brown, the Colorado Bar Association’s president, stresses that learning how to practice law doesn’t happen overnight. “It’s not something you can learn with an associate’s degree or 3,000 hours of training,” he says. “It is something that takes a great deal of practice and education.”

Despite early positive reviews of Washington’s experiment, at that January meeting Colorado’s subcommittee favored a wait-and-see approach while looking at other solutions for the pro se litigant issue. They include New York’s Court Navigator program, which pairs trained volunteers with pro se litigants to act as something like legal tour guides outside of courtrooms. The program is somewhat similar to Colorado’s four-year-old Self-Represented Litigant Coordinator program. About 125,000 litigants interacted with its staffers (called Sherlocks) and courthouse self-help centers in 2015. Why not just focus on expanding that program? James Coyle, the attorney regulation counsel for the Colorado Supreme Court (the group responsible for licensing and policing the state’s attorneys) wants to explore that idea as well as what his office can do to help pro se litigants get the justice they seek. “My function in all of this,” Coyle says, “is to keep throwing ideas out, and hopefully something will stick.”

Whatever Colorado officials decide to do, questions and concerns are likely to remain. “The difficulty,” says CLS’ Asher, a member of the subcommittee, “is how do you solve the crisis? And are our solutions really solutions, or just Band-Aids?”

In general, lawyers aren’t known for reworking their processes or for moving fast when they do, which is why it took Washington more than a decade to implement its LLLT program. “The legal profession is very change-resistant,” IAALS’ Kourlis says. “Lawyers drive looking in the rear-view mirror, looking at case precedent. Envisioning what could be is not necessarily part of lawyers’ thinking.” But, she adds, that’s where private-sector solutions can help.

For example, IAALS is facilitating the development of an app through which pro se litigants filing domestic cases can ask questions about what to expect in court or how to fill out forms. With DU, IAALS also helped to create the model that the independent nonprofit Center for Out-of-Court Divorce is based on. For a flat $4,500 fee, the center aims to help people, like Rayder, who are going through amicable divorces, and its services include family counseling, co-parent planning, and legal document drafting. If post-decree issues—everything that happens after a divorce is filed, including child custody plans and alimony payments—crop up that might make a friendly divorce a little less so, the center has mediation and coaching for $120 to $300 an hour.

The relatively low fees are made possible through grants but can also be achieved by finding attorneys, such as Boulder’s Bruce Wiener, who are willing to work for lower rates. Three years ago, Wiener founded Bridge to Justice, a nonprofit law practice that does “low bono” work (as opposed to “pro bono,” the term for volunteer legal help) for income-qualified clients. The model is one of the first of its kind in the country. “We represent a lot of single moms, but we represent a lot of fathers, too, and people who are one or two hardships away from poverty,” Wiener says. “They are in that doughnut hole where they make too much to qualify for government services but not enough to pay for an attorney.” He and two other attorneys charge $95 an hour for out-of-court work and $120 an hour for court appearances. Bridge to Justice has served more than 700 clients, many of them referrals from CLS, which doesn’t have the state-funded resources to assist in post-decree matters.

Wiener’s also quick to point out that unlike workers at similar law-school-based incubators, his staff members are all experienced attorneys who believe in providing fairly priced services to in-need clients. There’s something in it for the attorneys, too: By working at a nonprofit, they can qualify for student loan forgiveness programs. Bridge to Justice quells many of the LLLT subcommittee’s concerns that pro se litigants don’t have access to affordably priced licensed attorneys. “I think we’re scratching the surface,” Wiener says. “The need is so overwhelming, and I don’t think that need is going to be met.”

Which is why people like Kerry Rayder will continue to go it alone in Colorado courts, joining the more than 34,000 parties each year who file domestic cases here without an attorney. “I think it would have been helpful to have a navigator, or someone who would just sit down with you,” Rayder says in hindsight. “If you did it every day it would make sense, but most of us are in one-and-done situations. It wasn’t impossible, but it was frustrating, and they made it harder than it needed to be.”

Images courtesy of proadvocate.org and prose-litigants.org

William M. Windsor

I, William M. Windsor, am not an attorney. This website expresses my OPINIONS. The comments of visitors or guest authors to the website are their opinions and do not therefore reflect my opinions. Anyone mentioned by name in any article is welcome to file a response. This website does not provide legal advice. I do not give legal advice. I do not practice law. This website is to expose government corruption, law enforcement corruption, political corruption, and judicial corruption. Whatever this website says about the law is presented in the context of how I or others perceive the applicability of the law to a set of circumstances if I (or some other author) was in the circumstances under the conditions discussed. Despite my concerns about lawyers in general, I suggest that anyone with legal questions consult an attorney for an answer, particularly after reading anything on this website. The law is a gray area at best. Please read our Legal Notice and Terms.

www.LawlessAmerica.com — www.facebook.com/billwindsor1 — www.twitter.com/lawlessamerica — www.youtube.com/lawlessamerica — www.lawlessamerica.org

{jcomments on}